Shell, Ping, Pong, Shell: Part 1 — Shyll

Constructing a Covert ICMP Remote Shell and How to Unravel its Communications using Ghidra, Radare2, WireShark, Volatility3 and Python.

Shyll — Shell to Ping

Your every-day avid Linux enthusiast, researchers and analysts, professional software developers and even their omnipotent Network and System Administrators have all one thing in common: they have connected to a SSH Shell. Some maybe a telnet Shell, or a UART Shell.

A covert back door Shell is yet another Shell, except rather than it existing in plain-sight, it is hidden. The network traffic blends in the background as does the server process on the host machine.

Shyll (Shy-ll) is a covert Shell server that works over a reliable stream protocol established and facilitated using the ICMP IPv4 Protocol. Shyll supports multiple concurrent sessions from multiple remote machines, just like a regular SSH Server, but unlike an SSH Server, Shyll uses only ICMP Echo Requests to communicate between the client and server machine.

Later in this series, in Part 7, how Shyll works and how it is implemented is explained in detail. For now, the first few parts of this series details an approach to attack a covert back-door tool like Shyll.

Shyll (Shy-ll) is a covert Shell server that works … just like a regular SSH Server, but unlike an SSH Server, Shyll uses only ICMP Echo Requests to communicate between the client and server machine.

A Short Demonstration

Resources for this Series

If I have captured your attention and you are interested in following along this journey of practical code reverse engineering, memory forensics and scripting, then you might want a copy of Shyll to experiment and follow-along with.

Everything you need to follow along, including scripts to process data and the Shyll binary itself can be found in a github repository here:

https://github.com/JeremyWildsmith/shyll-demo

You will learn about the scripts contained in this repository as you progress through the article series!

About the Shyll-Demo Binary

The repository includes a limited version of Shyll called shyll-demo, which is slightly different than the version discussed in this series. While shyll-demo mirrors the full Shyll's binary file offsets, allowing you to easily follow along this guide in all steps, it comes with built-in restrictions. This restricted demo is provided in-place of the original shyll out of caution, although Shyll isn't malware it can be used in covert attacks. The shyll-demo binary lets you replicate every step in the article, but it can't be used as a remote backdoor like the original, unrestricted Shyll.

As discussed above, the “shyll-demo” binary has the following limitations:

The shyll-demo binary can only connect to and listen from localhost

The original Shyll spawns a bash session, shyll-demo just spawns a bc session (basic calculator interactive session)

Some auxiliary features such as process-hiding and keylogging have been removed out of shyll-demo

If you are a security researcher or educator and would like the original source code to Shyll for educational purposes only, please reach out and I can look at providing the original copy after some verification, but for following along and learning the demo version provided in the repository is completely sufficient.

Recovering Attack Logs — Pong to Shell

Imagine discovering a covert shell installed on your machine. Your immediate question would be: what did this shell do? What is the scope of compromise? This article series focuses on answering those questions by applying practical code reverse engineering, packet analysis, memory forensics and code instrumentation.

Any organization of significant size likely monitors and captures network traffic, and a packet capture recording provides a historical record of such covert back-door interactions. However, a raw packet capture is just noise if the protocol or encryption details are unknown, leaving the history of a covert shell’s communication buried and seemingly out of reach.

Fortunately, there is a way to reconstruct this traffic. It requires strategic analysis and the application of specialized tools that can transform the raw packets back into a meaningful communication stream.

a packet capture recording provides a historical record of such covert back-door interactions. However, a raw packet capture is just noise if the protocol or encryption details are unknown

The Indicators of Compromise

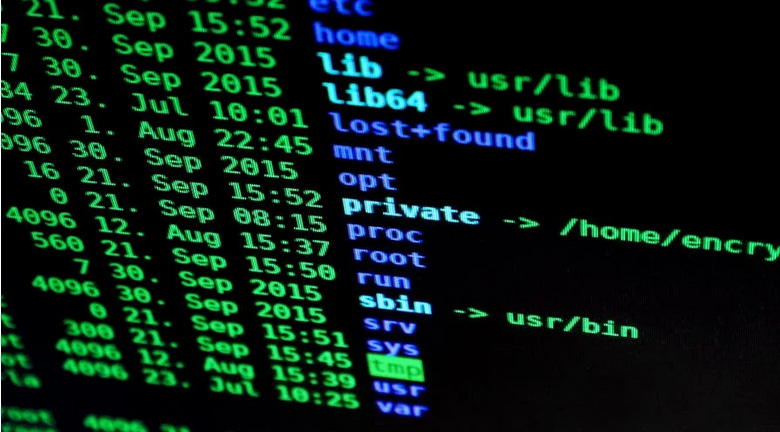

Before we start digging into Shyll and attempting to recover the network communication, lets look at some Indicators of Compromise which suggest the machine is compromised. There are a lot of indicators, but keep in mind this article focuses more on the reverse engineering and application of findings through reverse engineering to reconstruct traffic and is less concerned with detection or analyzing the compromised machine itself.

Packet Capture

Before diving into reconstruction, let’s examine some clear Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) visible within a Wireshark packet capture when Shyll is installed and activated.

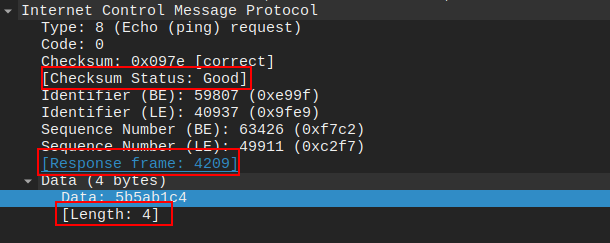

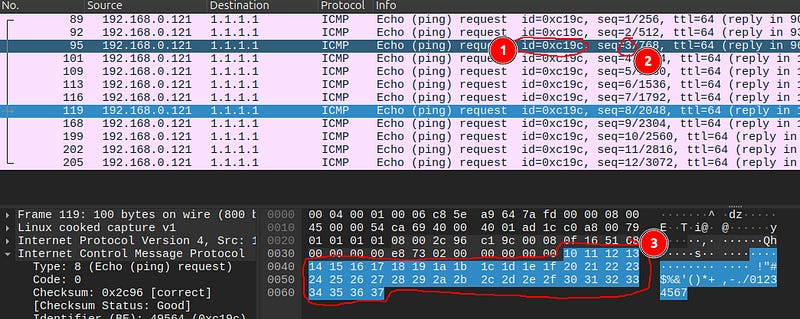

Looking at a single ICMP Echo Request apart of Shyll’s data-smuggling, a cursory glance suggests it is fairly normal. The ICMP Payload is small, the checksum is valid, and a valid accompanying response is found. WireShark’s expert system has no complaints about this ICMP Traffic.

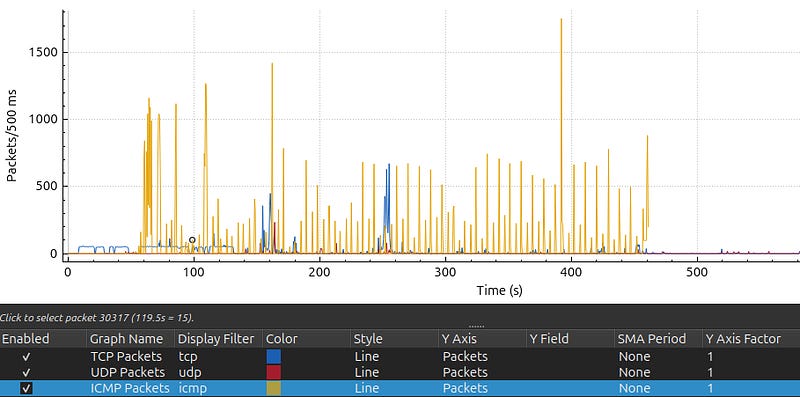

The indicators of compromise begin to appear when you consider the ICMP traffic in its’ totality. Without careful covert use of ICMP traffic to smuggle data in and out of the target, a profoundly high volume and spikes in traffic can be observed. This is largely due to the fact that a single packet, per the covert protocol, can only carry 16-bits of data. Which is not much data at all.

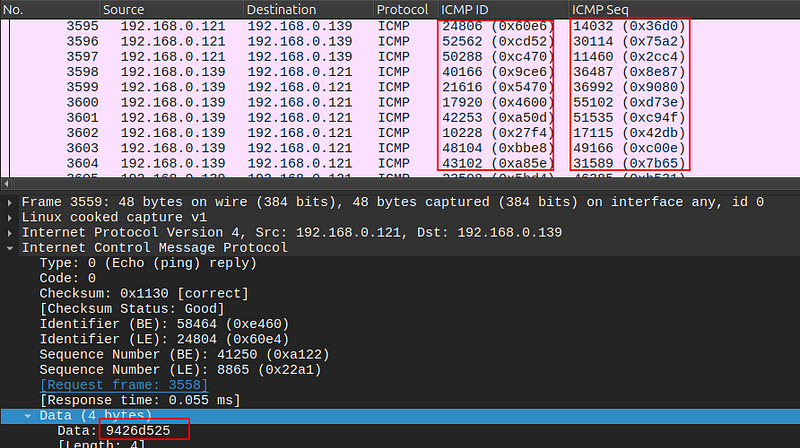

In addition, the ICMP Echo Request traffic, when contrasted against typical traffic observed from a ping command, reveals that this traffic in totality is very unusual.

Compare the above Echo-Request traffic generated by Shyll to what is seen in a typical ping request below:

In summary, the covert Shyll ICMP Echo-Request traffic stands clearly apart from a typical implementation and usage of Ping:

In typical ping command usage, the Echo ID usually remains consistent or re-uses a small range of IDs within a single session.

In a typical ICMP Echo-Request the Sequence Number increases sequentially; however, the Echo-Requests from Shyll traffic use a seemingly random Sequence Number.

The payload of Shyll’s Echo Requests are very small, but if you combine the payloads of adjacent Echo-Requests from Shyll, the calculated entropy is very high. This is very unusual compared to a typical ping request which has, as seen in above image of typical ICMP traffic, very uniform & sequential payloads.

Some of these indicators can be trivial to hide, for example in a real-case attack scenario you might throttle the ICMP Traffic to prevent such obvious spikes in ICMP Packets or use a NAT to obscure the source and destination of traffic which would distribute the concentration of ICMP Echo-Request traffic to and back from a single remote machine.

The indicators of compromise begin to appear when you consider the ICMP traffic in its’ totality.

Preserving State and Finding Encryption Keys

In accordance with accepted digital forensics practices, it is critically important that if a machine is found to be compromised and it is still running, you make the best efforts necessary to preserve the state of the machine prior to shutting it down or trying to analyze it, it may be your last chance to get critical information like encryption keys that become imperative to posses in future analysis.

Later in this series, we will be digging into a memory dump using Volatility to recover a critical piece of information necessary to complete our analysis (encryption keys.) We can marry the memory dump with our static analysis to find some highly valuable information. If we did not have this memory dump it would significantly impede our ability requiring us to resort to a brute-force approach that would be highly prohibitive.

make the best efforts necessary to preserve the state of the machine prior to shutting it down or trying to analyze it, it may be your last chance to get critical information like encryption keys

Rebuilding the Communications

Imagine you’ve captured packet communication from a remote attacker interacting with a backdoor on your machine. How can this traffic be analyzed to determine the scope of compromise, to determine the attacker’s actions? While a direct examination of the WireShark capture might not immediately reveal intelligible data, this scenario presents a fascinating opportunity for practical reverse engineering and scripting. It turns out, we can leverage components of the backdoor itself to analyze the packet capture and recover the full interaction log, thereby uncovering the complete details of the attack.

If I have captured your interest thus-far, follow me into Part 2, where we use Ghidra, Radare2 and Python to begin to uncover the hidden communications of Shyll.